- Accueil

- > La revue

- > Numéro 2

- > Imaginaire collectif slave et construction identit ...

- > Staging « Today’s Russia » : Le Pas d’acier and the Creation of a « New » Russian Idiom

Staging « Today’s Russia » : Le Pas d’acier and the Creation of a « New » Russian Idiom

Par Alixandra Haywood

Publication en ligne le 20 juin 2013

Résumé

As the first ballet to depict the Soviet Union, Serge Prokofiev’s Le Pas d’acier (1927) sought explicitly to depict « today’s Russia ». Staged by the Ballets russes, a Paris-based company well-known for its lavish productions often inspired by Russian mythology and ancient history, Le Pas d’acier was intended to reflect a different image of Russian culture : the new realities of Soviet life. The ballet’s scenario (commissioned by company director Serge Diaghilev, and conceived jointly by Prokofiev and the production’s designer Georgy Yakulov) features numerous symbols typical of Soviet propaganda, and contrasts heroic figures such as the Worker and the Sailor with a variety of unscrupulous characters representing pre-Revolution ways of life. In addition to depicting contemporary Russia, the ballet also endeavoured to create a modern Russian aesthetic, and the memoirs and correspondence of its creators reflect a shared understanding that Le Pas d’acier was not to be in the style of « Afanasiev’s fairytales » but rather a « new Russian idiom ». Nevertheless, a closer examination reveals that this new Russian idiom was quite rooted in the past and the creative team relied on hallmarks of pre-Revolution Russian imagery to infuse Le Pas d’acier with a recognisably national character. While Léonide Massine’s choreography was overtly inspired by old legends and fairytales, Prokofiev’s engagement with past archetypes of Russianness was more subtle, evident in the score’s traditional settings of Slavic folksongs and allusions to other recent and well-known musical depictions of the culture. Such juxtapositions between established and new conventions of Russianness occur throughout the ballet, and, as was keenly noted by the French and Russian press, achieved varying degrees of success. This paper examines the representations of Russianness in Le Pas d’acier, and, in addition to a close reading of the ballet itself, also considers external factors that may have shaped its message and reception including Diaghilev’s relationship with his homeland, the company’s financial dependence on its audience, and contemporary Franco-Soviet relations.

Будучи первым балетом, изображающим Советский Союз, « Стальной скок » Сергея Прокофьева стремился показать именно « сегодняшнюю Россию ». Реализованный « Русским балетом » - парижской компанией, известной своими пышными постановками, часто вдохновлёнными русской мифологией и древней историей, « Стальной скок » должен был отразить другой образ русской культуры, а именно - новые реалии советской жизни. Сценарий балета (который был создан совместными усилиями Прокофьева и художника-постановщика Георгия Якулова по заказу директора компании Сергея Дягилева) использует многочисленные символы советской пропаганды и противопоставляет таких героев как Рабочий и Моряк различным беспринципным персонажам, представляющим дореволюционную жизнь. Помимо попытки изобразить современную Россию, этот балет стремился создать новую русскую эстетику ; воспоминания и переписка его создателей отражают их взаимное согласие в том, что « Стальной скок » должен быть в стиле новой русской идиомы, а не Афанасьевских сказок. Тем не менее, при более внимательном рассмотрении оказывается, что корни этой новой русской идиомы уходят глубоко в прошлое, а творческий союз создателей балета, стремясь внести в балет узнаваемый национальный характер, полагался на отличительные признаки русских образов дореволюционной России. Если хореография Мясина была откровенно вдохновлена старинными легендами и сказками, то использование прототипов прошлого у Прокофьева более тонкое. Оно проявляется в обращении к традиционным cлавянским песенным оборотам и в других ссылках на хорошо известные условности музыкального изображения русской культуры. Такое чередование общепризнанных и новых средств передачи русского национального колорита пронизывает балет с переменным успехом, как было метко замечено французской и русской прессой. В настоящей статье рассматривается то, как русский национальный колорит был передан в «Стальном скоке». Помимо детального анализа самого балета, здесь исследуются внешние факторы, возможно, повлиявшие как на создание балета, так и на его рецепцию: отношение Дягилева к своей родине, финансовая зависимость компании от публики, а также франко-русские отношения той эпохи.

Le ballet Le Pas d’acier (1927) fut le premier à chercher à représenter expressément la Russie de l’époque. Mis en scène par les Ballets russes, Le Pas d’acier se distinguait des thèmes traditionnels abordés par la compagnie située à Paris en reflétant non pas l’histoire ancienne ou les mythes russes, mais plutôt les réalités quotidiennes sous le régime soviétique. Son scénario était une commande du directeur des Ballets russes Serge Diaghilev, auprès du compositeur Serge Prokofiev et de l’artiste Georgy Yakulov, qui ont collaboré à son écriture, en plus d’être responsables de la composition musicale et des décors respectivement. Le scénario présente de nombreux symboles typiques de la propagande soviétique et expose les différences entre des personnages héroïques, tels que le Matelot au bracelet et l’Ouvrière, et une variété de personnages immoraux qui représentent le mode de vie d’avant la Révolution. Non content de seulement représenter la Russie contemporaine, le ballet tentait aussi de créer une esthétique russe moderne, et les écrits des créateurs qui y ont travaillé reflètent une compréhension mutuelle : Le Pas d’acier ne serait pas dans le style « des contes d’Afanasiev » mais plutôt dans « un nouveau style russe ». Cependant, en l’étudiant de plus près, on voit que ce nouveau style russe avait ses racines fermement ancrées dans le passé et que ses créateurs se sont appuyés sur des symboles de l’iconographie russe typiques de l’époque d’avant la Révolution afin d’instiller dans Le Pas d’acier une identité nationale facilement reconnaissable. Bien que la chorégraphie de Léonide Massine ait été ouvertement inspirée par les mythes et l’histoire de la Russie ancienne, Prokofiev a pour sa part abordé des archétypes du caractère russe d’une manière plus subtile, comme le montrent ses arrangements traditionnels des chansons populaires slaves et ses allusions à d’autres récentes représentations musicales connues de la culture. Des juxtapositions de ce type, qui mettent en opposition les nouvelles conventions de la culture russe avec des symboles bien établis, se trouvent partout dans le ballet, et ont obtenu un succès variable, comme la presse française et russe l’ont bien fait remarquer. Cet article traite des représentations de la culture russe dans Le Pas d’acier par une analyse approfondie du ballet lui-même, mais aussi des facteurs externes qui auraient pu influencer son message et sa réception, notamment la relation entre Diaghilev et son pays d’origine, la relation financière qu’entretenaient les Ballets russes avec le public parisien, et les relations franco-russes de l’époque.

Mots-Clés

Texte intégral

Introduction

1In 1909, a fledgling ballet company known as the Ballets russes and their director Serge Diaghilev arrived in Paris. Over the course of the next five years, the Ballets russes would impress, and sometimes even shock, Parisian audiences, and cement its status as Europe’s premiere ballet company through a series of innovative works, the most successful of which emphasised the company’s exotic Russian roots by incorporating ancient Slavic legends and playing on French conceptions of Russian culture1. While the Ballets russes would go on to present a wide variety of programmes reflecting both the increasingly cosmopolitan composition of the company and the capricious tastes of Parisian audiences, the exotic depictions of Russian culture that characterised their earliest seasons (such as the well-known pair of ballets by Igor Stravinsky : L’Oiseau de feu and Le Sacre du printemps) continued to form a mainstay of the company’s repertoire. It was not until 1925, following a gradual renewal of French interest in Russian culture in the wake of the 1917 Russian Revolution, that the Ballets russes would turn their attention to a more contemporary image of the Slav in the ballet Le Pas d’acier.

2That Le Pas d’acier reflect contemporary life in Soviet Russia was of utmost importance to Diaghilev. Exoticism continued to be popular with French audiences and the 1920s saw the revival of French fascination with the activities and daily realities of the mysterious Soviet Union. Parisian newspapers and magazines featured headlines discussing Soviet political developments on their front pages almost daily2, and avant-garde Russian artistic movements like constructivism gained notoriety. This revitalised appeal, along with Diaghilev’s increasing preoccupation with his homeland3, created ideal circumstances in which the Ballets russes could return to the Russian-style ballets that had originally established its popularity before the war4. Russia had come back into fashion in Paris, but in a different incarnation ; the French image of exotic, fantastical Russia was dated and the company turned to images of contemporary Soviet culture in order to keep up with the new French expectations.

1. Staging ‘Today’s Russia’

3The ballet was the first in years to have an entirely Russian creative team, including Ballets russes veterans composer Serge Prokofiev (1891-1953) and choreographer (and former principal dancer) Léonide Massine (1896-1979)5, as well as special import Georgy Yakulov (1884-1928), an important artist active in the Moscow avant-garde. While Diaghilev had long been preoccupied with the nationalities of his choreographers and dancers6, extending this concern to other members of his creative team was unusual behaviour likely related to Le Pas d’acier’s specific subject matter. Foreign composers, writers and artists could write cosmopolitan ballets, but Russian ballets required Russian creative input.7 Furthermore, as the first ballet to depict the Soviet Union, Le Pas d’acier also encouraged Diaghilev to look beyond his usual network of Russian émigrés living in Europe and seek out an artist who had more recent experience with and understanding of contemporary Soviet life. As Diaghilev’s close friend and colleague Boris Kochno documented in his memoirs :

« Yakulov’s position as an established, leading figure in the Russian constructivist movement in Moscow served to provide valuable, first-hand insight to the rest of the ballet’s creative team, add an additional air of authenticity to the production, and circumvent potential criticisms that the ballet was conceived by cosmopolitan Russians long-distanced from the current realities of Soviet life8. »

4Anxiety regarding the public’s reaction to what had the potential to be an enormously controversial work was an immediate concern of almost the all members of Le Pas d’acier’s creative team. The ballet’s subject matter was inherently politically charged, and Diaghilev was hoping for a strong reaction. While he anticipated a backlash against its Bolshevik theme from the Russian émigré community in Paris, neither the demonstration nor the opening-night scandal he predicted materialised9. Diaghilev was also concerned about the Soviet response to the ballet, going so far as to contact Soviet ambassadors stationed in Europe to assure them that it was not meant to be a political statement10. Given his intention of eventually returning to his homeland, Prokofiev was particularly anxious about the public reaction. The composer’s first-choice collaborator was recent Russian émigré Pyotr Souvchinsky (1892-1985), an artistic patron and writer who Prokofiev believed had « unusual tact so as exactly to take the subject on to such a plane as to not infuriate people either here or there, and entirely to reflect contemporary Bolshevik life11 ». While Souvchinsky would not ultimately be involved with the production, Yakulov filled this requirement neatly, although he had his own reservations. Having spent time and presented exhibitions in Europe, Yakulov was familiar with Western perceptions of Russian art and culture, and consequently was wary of risking his « reputation by producing a Western ballet about Soviet life12 ».

5Le Pas d’acier’s central goal, however, was not to project an overtly partisan political stance, but rather to reflect contemporary Soviet life, and this aim is evident in Diaghilev’s instructions to the ballet’s creative team as well as in the work’s original scenario. In June 1925 the impresario emphasised in a letter to Prokofiev the importance of cultivating the French public’s new visions of Soviet Russia rather than returning to old stereotypes, writing : « No one’s interested in a Russian ballet based on Afanasyev’s fairytales or the life of Ivan the Terrible. You, Seryozha, must write a ballet about today’s Russia13 ».

6The ballet’s literal depiction of « today’s Russia » in the scenario was entrusted to Prokofiev and Yakulov, who quickly established « the transformation of the Soviet Union into an industrialised nation and the attempt to create a new society14 », as the ballet’s guiding narrative. This narrative was not to feature a depiction of the Bolsheviks themselves, but rather, as Prokofiev observed in a 1925 letter to Souvchinsky, « the Russian people under the rule of the Bolsheviks15 ». Prokofiev advocated a Spartan approach to the scenario, writing in the same letter to Souvchinsky that, « As concerns the subject itself, in essence, the less of it there is, the better ; the simpler it is, the bigger a role the music will play16 ».

7Nevertheless, a narrative did eventually emerge in Le Pas d’acier’s scenario. As outlined by Lesley-Anne Sayers and Simon Morrison, the ballet’s first act features the introduction of numerous stock revolutionary characters and symbols typical of Soviet propaganda of the period, and contrasts heroic Soviet figures like the Sailor and the Worker with opportunist and unscrupulous characters like swindlers and black marketeers representing « the old ways of life17 ». This contrast gains significance in Act 2, wherein the positively portrayed Soviet characters become factory workers and perform on an elevated platform, and the representatives of the old way of life are relegated to ground level18. The victory of the new ways over the old is realised through the quest of the Sailor and the Worker Girl to unite romantically amidst the utilitarian collective labouring of the workers in the factory. Sayers and Morrison assert that the pair’s ultimate unification in Act 2’s finale is rooted in « a celebration of their new identity as workers in harmony with the machine age », and that this is the scenario’s primary message19.

8While Diaghilev’s goal of depicting « today’s Russia » was clearly realised in Prokofiev and Yakulov’s original scenario, this was not the version Parisian audiences would see when the ballet was finally staged in 1927. After putting preparations for the ballet’s production on hold for nearly two years, Massine was brought on board as Le Pas d’acier’s choreographer, and his choreography and unusually extensive modifications to the scenario reveal a slightly different concept of the work. While the scenario and choreographic notation for the version that incorporated Massine’s changes has unfortunately been lost, other primary sources provide glimpses of the ballet that was actually performed. Although his 1968 autobiography indicates that he understood Le Pas d’acier’s intended purpose « to distil the essence of current social conditions in the new Russia20 », Massine’s work on the ballet was less unified in its direction, a development that worried both Prokofiev and Yakulov21. While the second act retained its twentieth-century setting, in Massine’s own words, « demonstrating the force and virility of Communist youth22 », the first act incorporated old legends and fairytales (such as the fight of Baba Yaga and the crocodile)23, detracting from the original concept of the ballet as a representation of the new, contemporary Russian culture. Massine’s allusions to ancient Russian mythology proved confusing and artificial for some critics24 ; instead of reinforcing the ballet’s Russian character, here the addition of more traditional, historical Russian elements took away from the work’s topicality.

9That Massine should draw on such classic markers of Russianness to characterise Le Pas d’acier was likely motivated by several factors. It is clear that he sought to infuse the ballet with an inherently Russian quality25, and this message was most easily communicated through conventional and familiar symbols. Le Pas d’acier depicted a new image of Russian life, one that had yet to fully establish its own aesthetic and stereotypes, and Massine perhaps felt obligated to reinforce its Russian character by rooting it in a recognisable tradition. Furthermore, Massine had no personal experience with this new lifestyle ; having left Russia in 1914, three years before the Revolution, his images of the country and its people were over a decade out of date, and he admittedly relied on the « essentially Russian » work already completed by Yakulov and Prokofiev for direction26.

2. A Contemporary Aesthetic

10In addition to depicting contemporary Russia, Diaghilev and his creative team also sought to infuse Le Pas d’acier with a modern Russian aesthetic. Yakulov and Massine strove to express this through constructivism, an abstractionist artistic movement originating in Russia shortly after the Revolution that rejected the idea of autonomous art-for-art’s-sake and emphasised instead a more practical art, often by portraying man and mechanisation non-representationally. While the influence of the constructivist movement could certainly be seen in Paris prior to the ballet’s premiere (including another 1927 Ballets russes production, La Chatte), the scale of Yakulov’s machines and platforms was unprecedented in Paris, inspiring a critic to remark in Le Ménestrel that all previous constructivist works were « but the first steps » towards Le Pas d’acier’s magnitude27. Though revolutionary in Paris, Yakulov’s designs were on par with other constructivist works being staged in Russia at the time28 ; thus in addition to providing the Ballets russes with an up-to-date understanding and representation of Soviet life for the ballet’s scenario, he also outfitted Le Pas d’acier with the latest Russian artistic fashions. Massine’s choreography in the ballet’s second act also reflected a constructivist influence, frequently using the dancers’ bodies (particularly those in the corps de ballet) to suggest the inner workings of a machine. As observed in the Parisian weekly arts journal Le Ménéstrel, « Each dancer was nothing more than an organ of transmission or rotation, an element in the grayness of modern machinery. All of the company screwed, hammered, twisted, meshed, and ground as though with a joyous desperation29 ».

11Prokofiev, seeking to re-establish his reputation with the Parisian public (with whom he had recently fallen out of favour30), interpreted Diaghilev’s instruction to write a ballet about « today’s Russia » as an occasion to re-examine his style. He described in his autobiography, « a turn towards the Russian musical idiom, this time not the idiom of Afanasiev’s fairytales, but one that could convey the spirit of modern times » as one of two major stylistic changes that influenced Le Pas d’acier’s score31. Critical reception of the ballet indicates that Prokofiev was indeed successful in conveying such a spirit, with critic Henry Malherbe observing in the daily newspaper Le Temps, for example, that :

« Those who are looking for the unseen and the unexpected would have found two reasons to be excited this week. Mr. Serge Prokofiev, who until now found inspiration only in exotic legends, has suddenly changed direction. In order to be more fashionable, he has hidden his natural disposition. He has invented a new musical orientalism : Soviet orientalism, the exoticism of machines32. »

12Prokofiev’s sudden shift of directions involved concrete musical changes as well. The composer himself notes in his autobiography that the second major stylistic change realised in Le Pas d’acier was a move « from the chromatic to the diatonic : this ballet... was in large measure diatonic and many of the themes were composed on the white keys only33 ». While Prokofiev retrospectively highlights these two changes as separate, his diaries from the time of Le Pas d’acier’s composition indicate that he in fact equated this new diatonicism with the new Russian idiom, describing the ballet’s score in October 1925 as « Russian, often impetuous, almost always diatonic, using the white keys. In short, white music to a red theme34 ».

13Though perhaps only intended as a play on words, Prokofiev’s description of the music as « white » is telling. Despite his criticism of Massine’s incorporation of old legends and fairytales, moments of Le Pas d’acier’s score reveal how deeply the composer also relied on hallmarks of pre-Revolution Russian music to infuse his new Russian idiom with a recognisably national character. It is worth noting that Prokofiev’s score was composed primarily during the first half of 1926, well before Massine was brought on board as the ballet’s choreographer the following year. While it is thus clear that Massine’s modifications to the scenario could not have influenced Le Pas d’acier’s music, it is indeed possible that Massine may have been encouraged by the inclusion of traditionally Russian elements in Prokofiev’s score and that this perhaps constituted part of the « essentially Russian character » he claims to have relied on.

14The most obvious and immediate of Prokofiev’s allusions to established tropes of Russianness is the ballet’s opening movement (Example 1). Ostensibly a quotation of a well-known factory song35, the diatonic melody that spans the movement’s first sixteen measures is set in a manner fit for a traditional folk song, evoking a conventional marker of nationalist style36. Divided into two halves, the first section consists of a fully orchestrated and widely scored unison setting of the melody, and the second its continuation harmonised with parallel motion in the inner voices, –imitating perhaps the solo verse-chorus structure typical of the style. The melody itself also alludes to being sung, featuring acciacaturas, slides between pitches, and specifically notated articulation mimicking the declamation of a casually sung folk song.

15It is the tonality of the melody and its setting that underline this passage’s allusion to the Russian folk tradition. Whereas the melody begins in C-major, its second phrase is decidedly in the relative natural minor (A), demonstrating « the quality of tonal “mutability” (peremennost’)... whereby a tune seem[s] to oscillate between two equally stable points of rest » that Richard Taruskin suggests characterises the Russian folk tradition, and later came to be a trope of Russian classical music as well37. The diatonic, parallel third harmonies of measures 8-10 also denote the number as Russian, emphasising the style’s deliberate lack of traditional Western harmonies and overarching V-I progression38. Although measures 12-15 contain strident, dissonant harmonies atypical of folk song harmonisations, Prokofiev’s clashing juxtaposition of chords is perhaps reminiscent of a different symbol of Russian music and a memorable, explicitly Russian production staged by the Ballets russes fourteen years earlier : Stravinsky’s Le Sacre du printemps. In stacking two tonal chords on roots a semitone apart (C7 and Db major), measure 12 perhaps alludes to the infamously dissonant juxtaposition of Eb7 and Fb major that features in the ballet’s second movement Les augures printaniers : danse des adolescentes. Thus, with each phrase of his setting of the Soviet worker-song, Prokofiev refers to recognisably Russian musical elements, layering allusions to different genres and periods, and moving from the unison simplicity and parallel third harmonies of Slavic folksong, through tonal mutability, to Stravinsky’s modern depiction of ancient Russian rites.

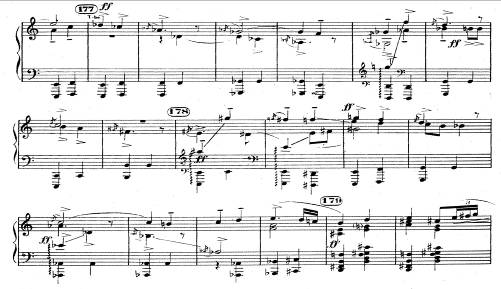

Example 1 : Entrée des personnages, measures 1-16 (piano reduction)39

16What is perhaps the most stereotypically Russian number in the ballet’s score occurs not during one of Le Pas d’acier’s two tableaux, but rather in the set-change during its intermission. Like Prokofiev’s opening, his brief Changement de décors also incorporates trademarks of the pre-Revolution Russian style established first by Mikhail Glinka (1804-57), and later by the members of the Kuchka40. Again alluding to folk-song, the number is framed by a widely and heavily scored pair of parallel melodic lines a third apart in the outer voices, and later supported from within by parallel moving harmonies in the inner voices. Such a scoring also references Glinka’s seminal opera A Life for the Tsar (1836), which, as described by Marina Frolova-Walker in her monograph Russian Music and Nationalism, was said to mark the creation of Russia’s new national music, and whose musical language would later come to symbolise the Russian nationalist style41. Prokofiev’s scoring of the Changement de décors emulates that of the final chorus of Glinka’s opera, which is also framed by a pair of parallel melodic lines a third apart in the outer voices.

17Predominantly in 6/4 time, the steady eighth-note motor of the movement’s rhythmic ostinato is sporadically disrupted with single measures of 3/4 or 5/4 time, and occasional quarter notes or quarter rests resulting from rhythmic augmentation. The overall effect is a metric irregularity that finds few equivalents elsewhere in the ballet’s generally steady, mechanical structure. While the movement’s scoring is primarily full and powerful, the ostinato’s last iteration comes quietly in pizzicato strings, perhaps another allusion to Russian folk music through an imitation of one of its most famous instruments : the balalaika. Furthermore, the ostinato itself can also be read as a marker of Russianness ; as Taruskin observes, the principle of ostinato formed a crucial element of Russian art music and appears in numerous iconic Russian nationalist works of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries42.

18It is interesting that the music of Le Pas d’acier that is most rooted in the conventional Russian aesthetic accompanies what Lesley-Anne Sayers deems the ballet’s strongest demonstration of the contemporary constructivist approach43. Sayers describes Massine’s unconventional use of dancers in full costume to facilitate the set change during the intermission as exemplary of the concepts of transformation and economy of means that underpin the Russian constructivist movement44. These concepts are also present in the movement’s defining musical feature, for in addition to being traditional, the ostinato principle is also an inherently economical practice, repeating, reusing and transforming one small motive into a variety of new possibilities. The music of the Changement de décors thus reflects both the section’s constructivist concept as well as a more conventional musical depiction of Russianness: old and new Russian styles had clearly grown from the same seed.

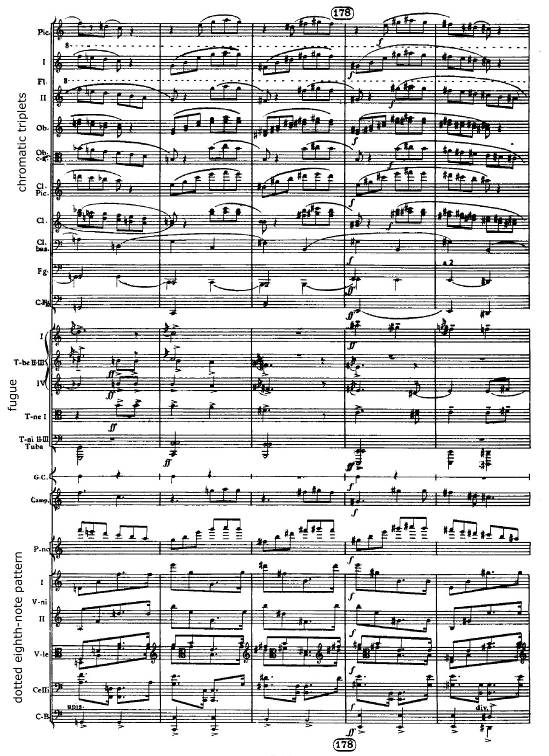

19As with the ballet’s choreography and narrative structure, the music of Le Pas d’acier’s second act drew less on established tropes of Russian nationalism, turning instead to the constructivist ideals of work, machinery, and transformation for inspiration. Beginning with the intermission’s Changement de décors described above, each of the ballet’s remaining movements becomes increasingly heavily textured, rhythmically complex and dissonant. The work’s final movement sees the return of many of the ballet’s earlier themes, including the factory song that opens the first act. The song’s return, however, is set in an entirely different manner than its original appearance. The long, unison phrases of the opening have been transformed into a fragmented, polytonal fugue in the brass (Example 2), and the gentle parallel harmonies replaced with two layers of competing rhythmic figuration : chromatic triplets in the woodwinds, and a dotted eighth-note pattern in the strings (Example 3).

Example 2 : Finale, fugue, rehearsals 176- 179 (piano reduction)45

Example 3 : Finale, layered, rhythmically complex texture (full score beginning three measures before rehearsal 178)46

20Here another connection can be made between Prokofiev’s new Russian idiom and pre-established conventions of Russian style ; the highly layered, polyrhythmic and dissonant character of the ballet’s second half is also possibly another allusion to Stravinsky’s Le Sacre du printemps, which similarly features superimposed ostinatos within an extremely dense texture and dissonant setting. Interestingly, this is not the only link between Le Pas d’acier and Stravinsky’s early Ballets russes productions. Sayers and Morrison suggest that the puppet-like, controlled choreography of Le Pas d’acier alludes to the movements of the puppet characters in the 1911 ballet Petrushka47. This comparison not only roots the ballet in an earlier, recognisably Russian tradition with which Parisian audiences were familiar, but also accentuates the new, industrial character of Soviet Russia by drawing a parallel between the man-controlled puppets of Petrushka and the workers of Le Pas d’acier controlled by machine.

Conclusion

21Such allusions to classic hallmarks of the Russian national style can be found throughout Le Pas d’acier, especially in the ballet’s first act. While they went generally unnoticed by European critics, it seems as though Russian critics were well aware of Prokofiev’s reliance on older, conventional tropes, criticising his score as having « nothing new », being « too contrived » and remarking specifically that it consisted « too much of the “white keys”48 ». Although Prokofiev thought « white music » – both the white of the keyboard and the political movement49 – an integral part of his new Russian idiom, the ballet’s reception implied otherwise.

22European reviews of the ballet were divided between criticisms of its first act as « artificial » and a « mockery »50 and nearly universal praise accorded its second. This can perhaps be partially attributed to the different methods in which Prokofiev (and his fellow collaborators) engaged with tradition and how they chose to relate contemporary Russia to the one with which they and their audiences were more familiar. Prokofiev’s use of older, established conventions of Russian music to fortify his new Russian idiom was most successful when he drew on concepts and characteristics that were common between old and new.

23Diaghilev’s goal of staging « today’s Russia » required a musical depiction that was both obviously contemporary, and explicitly Russian. While Prokofiev’s new Russian idiom (along with the constructivist elements of Yakulov’s design and Massine’s choreography, and the ballet’s unambiguously contemporary setting) met the first requirement, he was required to reach into the past for the second. Contemporary cultures were more superficially similar than their predecessors, and lacked the recognisably nationalist character of works based on mythology or ancient history. Prokofiev’s allusions to Russian folk styles, nineteenth-century tropes of Russian nationalist music, and the early exoticised Russian productions of the Ballets russes rooted Le Pas d’acier in the Russian tradition. Russian tropes of the past here reinforce the depiction of the present, and a contemporary, modish setting breathes new life into older nationalist stereotypes. It is the presence of both old and new that is of importance in Le Pas d’acier : the ballet fuses the conventional with the contemporary in order to create a new Russian idiom that retained the rich and comprehensible symbolism of tradition.

Bibliographie

Bibliography

Bowlt, John E., « Constructivism and Russian Stage Design », Performing Arts Journal, vol. 1 no. 3, 1977, p. 62-84.

Frolova-Walker, Marina, Russian Music and Nationalism From Glinka to Stalin, London, Yale University Press, 2007.

Garafola, Lynn, Diaghilev’s Ballets russes, New York, Oxford University Press, 1989.

Grigoriev, Serge. The Diaghilev Ballet, Vera Bowen (trans. and ed.), London, Constable and Company Ltd., 1953.

Kochno, Boris, Diaghilev and theBallets Russes, Adrienne Foulke (trans.), London, Allen Lane the Penguin Press, 1971.

Massine, Léonide, My Life in Ballet, Phyllis Hartnoll and Robert Rubens (eds.), London, Macmillan & Co. Ltd., 1968.

Melville, Joy, Diaghilev and Friends, London, Haus Publishing, 2009.

Nice, David, Prokofiev: From Russia to the West 1891-1935, New Haven, Yale University Press, 2003.

Press, Stephen., Prokofiev’s Ballets for Diaghilev, Aldershot, Ashgate Publishing Limited, 2006.

Prokofiev, Sergei, Le-Pas-d'acier : ballet in deux tableaux op. 41, réduction pour piano à 2 mains par l’auteur, Berlin, Édition Russe de musique, 1928.

Prokofiev, Sergei, Le-Pas-d’acier : Opus 41, Ballet in Two Scenes, London, Boosey & Hawkes, Inc., 1986.

Prokofiev, Sergei, Sergei Prokofiev Soviet Diary 1927 and Other Writings, Oleg Prokofiev and Christopher Palmer (trans. and eds.), London, Faber and Faber Limited, 1991.

Sayers, Lesley-Anne, « Re-discovering Diaghilev’s Pas d’acier », Dance Research :The Journal of the Society for Dance Research, n. 18, 2000, p. 163-185.

Sayers, Lesley-Anne and Simon Morrison. « Prokofiev’s Le-Pas-d’Acier : How the steel was tempered », in Neil Edmunds (ed.), Soviet Music and Society under Lenin and Stalin, Abingdon, Routledge Curzon, 2004, p. 81-104.

Scheijen, Sjeng, Diaghilev : A Life, Jane Hedley-Prôle and S. J. Leinbach (trans.), London, Profile Books Ltd., 2009.

Taruskin, Richard, Defining Russia Musically, Chicester, Princeton University Press, 1997.

Notes

1 I would like to extend my sincere thanks to Anthony Phillips for generously sharing his still in-progress English translation of Prokofiev’s diaries from 1925-27. I am also grateful to Marina Frolova-Walker for her assistance and guidance with this project, as well as Steven Huebner for his help in editing and refining it.

2 During the week of Le-Pas-d’acier’s premiere (5-11 June 1927), for example, the front page of Le-Figaro contained at least one headline discussing Soviet politics or life each day.

3 This preoccupation is well documented by Diaghilev’s numerous biographers. For example, Diaghilev’s close friend and colleague Serge Grigoriev recalls the impresario’s « terrible nostalgia for Russia » during this period (The Diaghilev Ballet, trans. and ed. Vera Bowen, London, Constable and Company Ltd., 1953, p. 237, while Joy Melville describes his large collection of Russian literature and interest in returning from Europe (Diaghilev and Friends, London, Haus Publishing, 2009, pp. 234-237).

4 It is worth noting that despite the Ballets russes’ huge initial success in Paris, the company struggled during the years following the war as competing companies emulating their successful model (such as the Ballets suédois and the Ballet Ida Rubenstein) began to appear and the company lost its local monopoly on contemporary ballet. This competition reached its peak during the mid-1920s, so the contemporaneous renewal of Parisian interest in Russian culture proved especially timely for Diaghilev, who could once again capitalise on the company’s Russian origins.

5 Name changed in 1916 from Miassin to Massine to facilitate English pronunciation. (See Léonide Massine, My Life in Ballet, ed. Phyllis Hartnoll and Robert Rubens, London, Macmillan & Co. Ltd., 1968, p. 81.)

6 As the Ballets russes became increasingly established in Paris and its connections to the Russian dance community diminished, the company was forced to engage foreign dancers to fill out its roster. These new European recruits were not only subjected to a rigorous immersion in the Russian culture and tradition of the company, but were also given new Russian surnames and encouraged to cultivate Russian personas in order to maintain the illusion that the company was still primarily Russian.

7 As Diaghilev explained to Prokofiev in a letter regarding Le Pas d’acier’s basic concept : « If I needed a foreign ballet I’d ask Auric. » (Prokofiev, diary entry 22-June-1925. Quoted and translated in Sjeng Scheijen, Diaghilev : A Life, trans. Jane Hedley-Prôle and S. J. Leinbach, London, Profile Books Ltd., 2009, p. 401. Georges Auric (1899-1983) was the French composer responsible for the scores of two previous Ballets russes productions : 1924’s French-style ballet Les Fâcheux and 1925’s Les Matelots.

8 Boris Kochno, Diaghilev and the Ballets Russes, trans. Adrienne Foulke, London, Allen Lane the Penguin Press, 1971, p. 264.

9 Grigoriev mentions the feared demonstration, p. 238 and Scheijen the predicted opening night scandal, p. 401.

10 Scheijen, p. 403.

11 Letter from Prokofiev to Souvchinsky, 24 June 1925. Published in Alla Bretanitskaya, Pyotr Souvchinsky I yevo vremya, Moscow, Kompozitor, 1999, p. 99 ; quoted and translated in David Nice, Prokofiev : From Russia to the West 1891-1935, New Haven, Yale University Press, 2003, p. 215.

12 Yakulov, Unpublished Russian letter to Prokofiev 12-October-1925, Prokofiev Archive, London. Quoted and translated in Lesley-Anne Sayers and Simon Morrison, « Prokofiev’s Le-Pas-d’Acier : How the steel was tempered », in Soviet Music and Society under Lenin and Stalin, ed. Neil Edmunds, Abingdon, Routledge Curzon, 2004, p. 84.

13 Prokofiev, diary entry 22-June-1925. Quoted and translated in Sjeng Scheijen, Diaghilev : A Life, trans. Jane Hedley-Prôle and S. J. Leinbach, London, Profile Books Ltd., 2009, p. 401.

14 Sayers and Morrison, p. 85.

15 Letter from Prokofiev to Souvchinsky, 24 June 1925. Published in Bretanitskaya, p. 99 (quoted and translated in Nice, p. 215).

16 Ibidem, p. 99 (quoted and translated in Nice, p. 215).

17 For an itemised analysis of such symbolism and the ballet’s allusions to iconic Soviet works of art, see Sayers and Morrison, pp. 85-86.

18 Ibidem, p. 85.

19 Ibidem, p. 86.

20 Massine, p. 171.

21 For a discussion of Prokofiev and Yakulov’s anxiety regarding Massine’s creative changes, see Sayers and Morrison, p. 85. Most telling is a telegram from Prokofiev just a few weeks before the ballet’s premiere urging Yakulov to « come soon or it will be too late ». (29 April 1927, Prokofiev Archive, London. Quoted and translated in Sayers and Morrison, p. 85.)

22 Massine, p. 172.

23 Stephen Press, Prokofiev’s Ballets for Diaghilev,Aldershot, Ashgate Publishing Limited, 2006, 214. Prokofiev’s diary entries from 9-10 April 1927 also mention Massine’s rejection of the scenario and incorporation of Baba-Yaga’s fight with the crocodile.

24 For example, Malherbe in Le-Temps (15-June-1927) : « L’interprétation est un peu trop articificieuse. La raillerie nous confond. »

25 Such as his use of « strenuous character movements to suggest the Slav temperament » (Massine, p. 172).

26 Massine, p. 172.

27 Schaeffner, Le-Ménestrel (17-24-juin-1927) : « Les “constructions” [...] n’étaient qu’un premier pas vers les véritables constructions de Georges Iakuloff. » (Unless otherwise specified, all translations from the French are the author’s).

28 For an excellent account of constructivist stage design during this period, including a description of the movement’s presence in both large Russian cities and Paris, see John E. Bowlt’s article « Constructivism and Russian Stage Design » in Performing Arts Journal, vol. 1, N 3, Winter 1977, p. 62-84.

29 Schaeffner, Le-Ménestrel (17-24-juin-1927) : « Chaque danseur, chaque danseuse n’est plus qu’un organe de transmission, de rotation ou de choc dans la grisaille de la machinerie moderne. Toute la troupe de ballet visse, martèle, se tord, s’engrène, broie comme avec un joyeux désespoir. »

30 Press describes Prokofiev’s struggles with the fickle Parisian public during the period of Le Pas d’acier’s composition, p. 205.

31 Sergei Prokofiev, Sergei Prokofiev Soviet Diary 1927 and Other Writings, trans. and ed. Oleg Prokofiev and Christopher Palmer, London, Faber and Faber Limited, 1991, p. 278.

32 Henry Malherbe, Le-Temps (Paris, 15-June-1927) : « Le public qui cherche l’inédit, l’inattendu, aura trouvé cette semaine deux raisons d’être stimulé. M. Serge Prokofieff, qui jusqu’à présent ne s’était inspiré que de légendes exotiques, a brusquement changé de direction. Il a masqué son naturel pour se mettre plus à la mode. Il a inventé un nouvel orientalisme musical : l’orientalisme soviétique, l’exotisme mécanique. ».

33 Prokofiev, Prokofiev Soviet Diary 1927 and Other Writings, p. 278.

34 Prokofiev, diary entry 16-October-1925. Quoted and translated in Scheijen, p. 403.

35 While it is widely referred to as a factory song, no one has as of yet discovered the original.

36 Press discusses Prokofiev’s folk-like, Kuchka-inspired setting of the factory-song briefly, pp. 231-232.

37 Richard Taruskin, Defining Russia Musically, Chicester, Princeton University Press, 1997, p. 133.

38 Taruskin writes of Russian composers’ (such as Balakirev) « avoidance of dominant harmony—this at a time when advanced Western (read : Wagnerian) harmonic practice was based on ever more emphatic dominant prolongations. » (Taruskin, p. 133). Frolova-Walker similarly describes the common perception of Russian music as harmonically distinctive (via an emphasis on plagalism) from the V-I progression so pervasive in Western music (Marina Frolova-Walker, Russian Music and Nationalism From Glinka to Stalin, London, Yale University Press, 2007, pp. 106-107).

39 Prokofiev, Le-Pas-d’acier : ballet in deux tableaux op. 41, réduction pour piano à 2 mains par l'auteur, Berlin, Édition Russe de musique, 1928, p. 1.

40 The Kuchka (known also as « The Mighty Handful » or « The Mighty Five » in English) are a group of five nationalist composers including Balakirev, Rimsky-Korsakov, Mussorgsky, Borodin and Cui.

41 Frolova-Walker, p. 58-61.

42 Taruskin, p. 117.

43 Lesley-Anne Sayers, « Re-discovering Diaghilev’s Pas d’acier », Dance Research : The Journal of the Society for Dance Reserach no. 18, October 2000, p. 169.

44 Ibidem, p. 169.

45 Prokofiev, Le-Pas-d'acier : ballet in deux tableaux op. 41, réduction pour piano à 2 mains par l’auteur, p. 58.

46 Prokofiev, Le-Pas-d’acier : Opus 41, Ballet in Two Scenes, London, Boosey & Hawkes, Inc., 1986, p. 222.

47 Sayers and Morrison, p. 99.

48 Nikolai Myaskovsky, Russian letter to Prokofiev 30 May 1928. Quoted and translated in Sayers and Morrison, p. 100.

49 It is worth noting briefly Prokofiev’s allegiance to the « white » political movement. As David Nice has described, despite Prokofiev’s geographical removal from his homeland, « he continued to have faith in the victorious regime ; his liberal mother had thrown in her lot almost involuntarily with the Whites. », Nice, p. 169.

50 Malherbe, Le-Temps (Paris, 15-June-1927) : « L’interprétation est un peu trop articificieuse. La raillerie nous confond. ».